It was such a privilege to be invited by WEAll Aotearoa to participate in a webinar on post growth business alongside two heroes of mine, Melanie Rieback, CEO/Co-founder of Radically Open Security, and Erinch Sahan, business and enterprise lead at the Doughnut Economics Action Lab. My thanks to Gareth Hughes, Sally Hett and Jessica Lavelle of WEAll.

My slides and presentation notes are below.

Presentation begins:

Hi, my name is Jennifer Wilkins. I research, advise and advocate for post growth business transformations. My practice goes under the name of Heliocene. I’m going to discuss the global macroeconomic backdrop to post growth transitions, the change that’s required in rich nations, and how industries such as food, housing and tourism might experience that change.

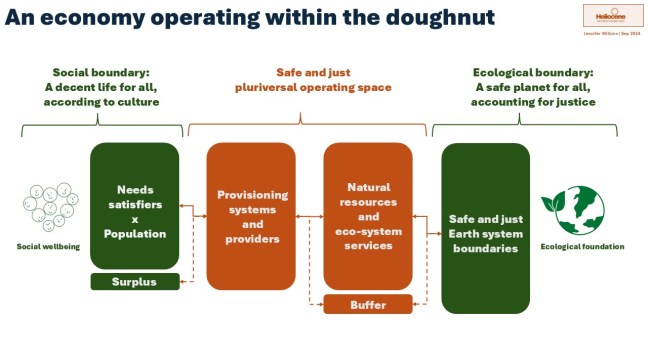

Post growth means operating within a holistic set of social and ecological boundaries. These are ethical boundaries: above a social foundation for a civilised humanity that meets people’s basic needs and beneath an ecological ceiling that marks out the edges of a planet that’s safe for humanity. We understand this as the Holocene epoch in which we’ve been living for the last 12,000 years.

These two boundaries are common denominators across global society, but there are many different worldviews that think beyond these basics.

Reference: Kate Raworth, 2017

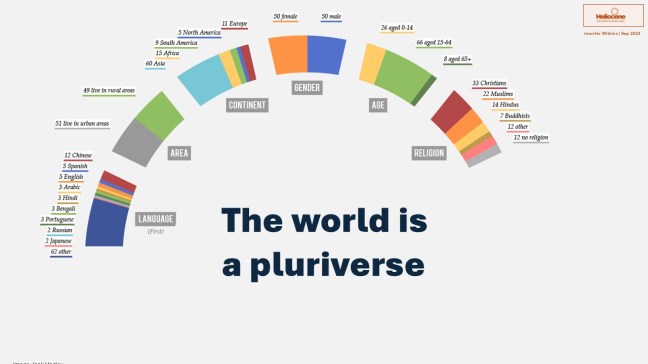

In fact, the world is a pluriverse. Humanity is diverse, with multiple languages, cultures, religions and living environments – so there are innumerable concepts of living a good life within nature.

Image source: Jack Hagley

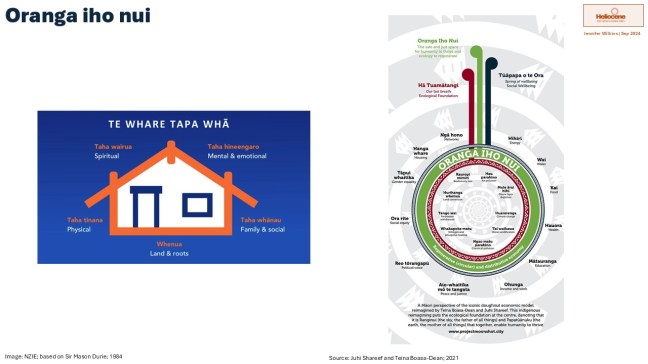

For instance, Māori have described their view of a good life on a safe planet using several models. The example on the left, very familiar to New Zealanders, is Te Whare Tapa Whā, the wellbeing meeting house, designed by Sir Mason Durie in the 1980s. Compared to Doughnut Economics, this model adds relationality or roots to the environmental, and it adds spiritual and emotional dimensions beyond the social. The example on the right is the Māori perspective on Doughnut Economics, depicted as Te Takarangi, the spiral of creation, in which the land is the foundation and social wellbeing springs up from the land.

References: Te Whare Tapa Whā by NZIE, based on Sir Mason Durie, 1984; Te Takarangi by Juhi Shareef and Teina Boasa-Dean, 2021

Going back to Doughnut Economics basics, a sustainable economy operates within a safe and just pluriversal operating space. It enables a decent life for all, according to culture. And a safe planet for all, accounting for justice.

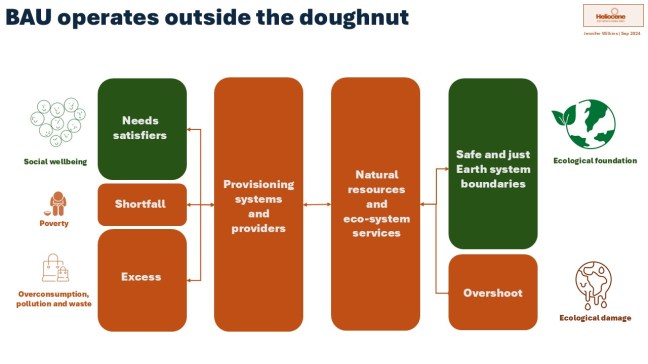

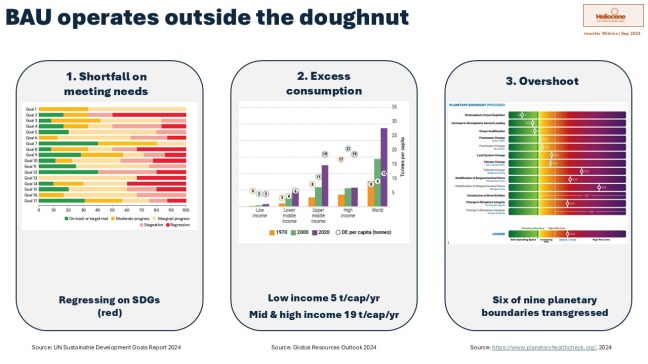

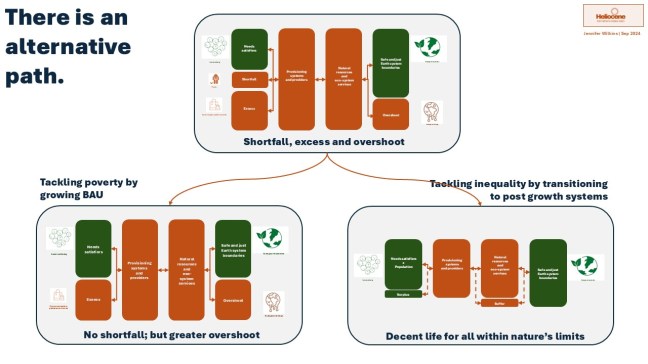

Our current global economy or business-as-usual (BAU), taken as a whole, operates beyond the walls of the doughnut. We are operating in shortfall – our provisioning systems are not distributing essential goods to where they are needed. We are also operating in excess – our provisioning systems are producing things far beyond what is needed for a good life. And we are operating in overshoot – our operating systems are extracting and polluting to an extent that the planet is becoming unsafe for people, particularly the vulnerable and the blameless.

The evidence for this is stacking up.

Chart 1: We are failing on all the SDGs. It’s particularly shameful to see regression on goal 2, to eradicate hunger, considering the global food system produces 6,000 human edible calories per person per day, and the average person needs around 2,200.

Chart 2: Unequal and excessive resource consumption is worsening. Average resource use is currently 12 t/cap/year. Some societies use as much as 19 t/cap, while some use as little as 5 t/cap. Back in 1970, before the world went into overshoot, the global average was 8 t/cap, about 2/3 of today’s use per capita.

Chart 3: Only 3 of nine planetary boundaries have not been transgressed, and ocean acidification may have crossed the boundary.

References: UN Sustainable Development Goals Report 2024; Global Resources Outlook 2024; Planetary Healthcheck 2024

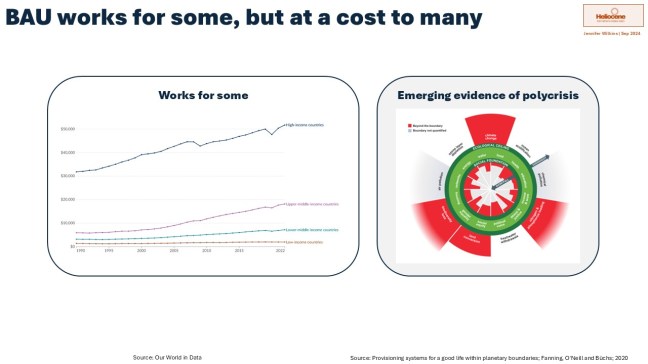

The problem is that BAU works for some but at a cost to many. High income countries have become richer, faster than other groups. At the same time, we see evidence of a polycrisis in which global issues are amplifying.

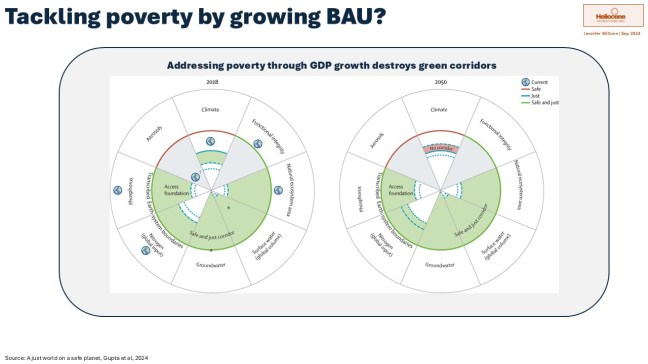

One persistent mainstream assumption is that we simply need to keep greening and growing BAU, because that will simultaneously mitigate climate change and raise global incomes above a poverty line. This has been tested and found to be a flawed assumption.

References: Our World in Data for GDP/capita; Provisioning systems for a good life within planetary boundaries, Fanning, O’Neill and Büchs, 2020

A paper published two weeks ago by a large group of climate scientists and economic modellers found that if BAU is grown enough by 2050 to tackle global poverty, we will irreversibly overshoot our climate boundary and reduce other safe corridors. We would, once and for all, lose the Holocene conditions in which humanity has thrived.

References: A just world on a safe planet, Gupta et al, 2024

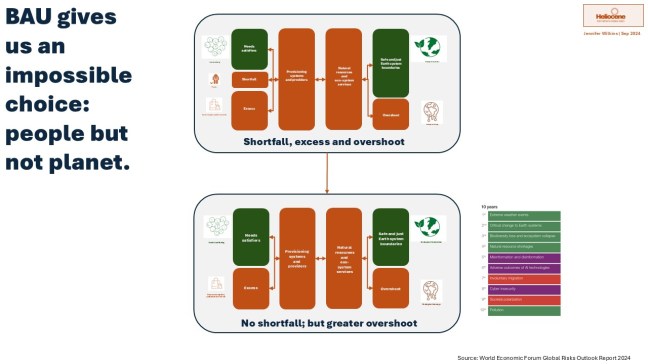

BAU gives us an impossible choice. Eradicate the poverty shortfall, but irreversibly transgress environmental boundaries. Considering this dilemma, it is unconscionable to choose to grow BAU to enrich the already rich, as all OECD governments are striving to do. The 10-year risk profile shows that we already expect this to happen. It is well understood that BAU is destructive and that systemic risks will affect all businesses, physically and reputationally. We would not choose to do this, so we must believe it is inevitable. Is it inevitable? Or is there another way?

The post growth movement believes there is an alternative path. We can choose not to grow BAU, but to change global operating systems to eradicate both the shortfall in distribution and the excess of unnecessary production and, in so doing, shift the global economy to within ecological boundaries.

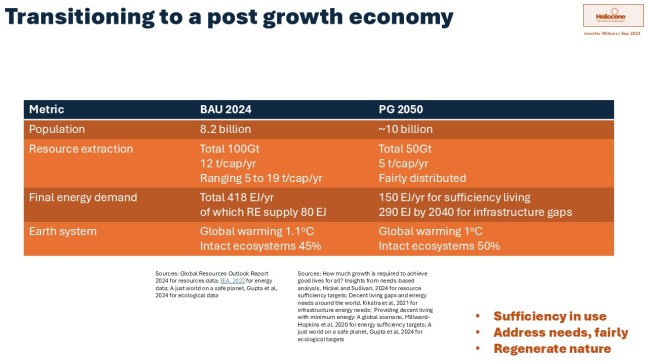

This is possible, but difficult. Some bottom-up post growth scenarios show the most ambitious extent to which sufficiency could be adopted. They are not technologically speculative scenarios; all the necessary household and industrial technologies already exist. They show that it is possible to live a very basic decent life using around 5 tonnes of resources and 15 GJ of energy per person per year. This is the lowest resource and energy scenario for sufficiency lifestyles only. Extra energy would be required to build the gaps in infrastructure needed to deliver this scenario (in equivalence) worldwide.

References:

BAU 2024 – Global Resources Outlook Report 2024 for resources data; IEA, 2022 for energy consumption data; A just world on a safe planet, Gupta et al, 2024 for ecological data

PG 2050 – How much growth is required to achieve good lives for all? Insights from needs-based analysis, Hickel and Sullivan, 2024 for resource sufficiency needs; Decent living gaps and energy needs around the world, Kikstra et al, 2021 for infrastructure energy needs; Providing decent living with minimum energy: A global scenario, Millward-Hopkins et al, 2020 for energy sufficiency needs; A just world on a safe planet, Gupta et al, 2024 for ecological boundaries

A PG transition aims to shift industries and communities towards sufficiency and to deepen fairness within the economy. At the same time, we need to regenerate nature since this maximises the safe and just operating space within the doughnut.

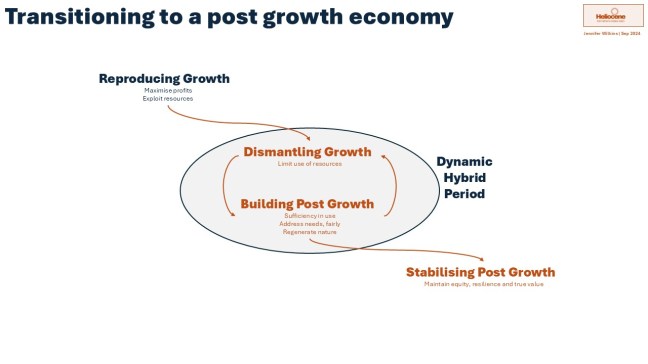

To make this bold transition come about, we must do two things at the same time: dismantle the rules of BAU (retaining some continuity, of course), and build a post growth economy from the ground up. This creates a dynamic hybrid period as we shift between the old and new paradigms.

Industries must navigate and negotiate opposing forces between growth and post growth thinking.

Ultimately, businesses must decide which future looks best and support it.

At the heart of it, industry transformation is going to pivot around the question of who gets to decides what gets produced. Under BAU rules it is exclusively the owners of capital. Under post growth rules participative economic democracy is key.

We, in the GN, will constantly be seeking ways to live well on far less, which is an opportunity for innovation. Industries will also be expected to deliver more for those who need it, to satiate global needs, which opens up new markets but may reduce profit margins. This would not be as problematic under less capitalistic business models.

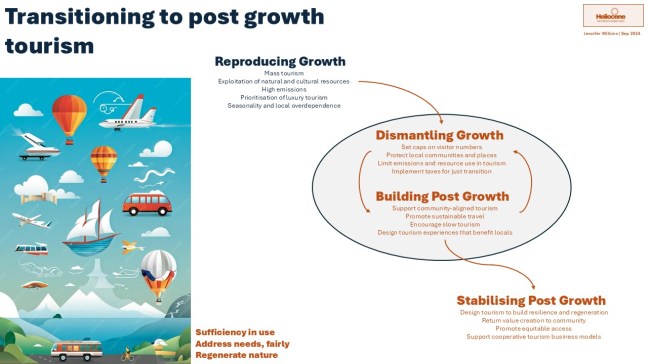

Here are some examples of industry transformations.

It starts with a recognition of the settings and methods that reproduce growth every day.

Dismantling growth is a forceful change to impose resource limits. Expect lots of regulatory change and legal challenges to make them happen.

Post growth enterprises and provisioning systems are going to be built through social, technological and funding innovations. These are the areas of opportunity in the 21st century economy. But the opportunity is not for high financial returns, it’s for high social and environmental returns.

And as post growth economies take shape, we can expect to see efforts to stabilise them, such as codifying certain rights into law. Generally, to make this work, economic focus will shift from organisations and the state, to community networks and the bioregion.

To finish, here’s a quick recap of the keywords I’ve mentioned.

Boundaries – there are two, the social and ecological.

Pluriverse – there are many diverse, unique worldviews that add more layers to these boundaries.

Participation – is key to overcoming the grip of capitalism on production decision making.

Sufficiency and fairness – are vital when it comes to limiting use of resources and energy.

Regeneration – restore Earth to Holocene conditions in which we are safe as a species and a global society.

Thank you. Ngā mihi nui.

Presentation ends.