In an age when economic growth is slowing in wealthy economies, New Zealand’s political and economic systems stay tethered to the promise of prosperity through growth—and falter when growth trickles out. Yet, when pursued blindly, growth can undermine the very prosperity we believe it should boost. It’s time for a national conversation about the rising risks of growth and the opportunities beyond it. This essay walks through the arguments and lands on a precautionary conclusion: we must cultivate an option for New Zealand’s prosperity without growth.

Jump to: Prosperity is the goal | New Zealand is rich | Growth is a political pursuit | Pro-growth policies aren’t reversing growth’s slowdown | Productivity—the magic bullet New Zealand can’t find | Short-term growth versus long-term prosperity | Good quality growth—various pathways to an ideal | Green growth—is it even possible? | Global growth—what could go wrong? | Growth-dependent wellbeing undermines resilience | Cultivating a new option for prosperity—without growth

Prosperity is the goal

The government of Aotearoa New Zealand is Going for Growth—a strategy that’s hardly new. For decades, successive governments have placed their faith in economic growth as the key to national prosperity. The logic is simple and widely accepted: economic growth—measured by an increase in gross domestic product (GDP), the value of goods and services produced—creates jobs, raises wages and improves living standards, thereby enhancing wellbeing. Business growth further drives profits, which generate wealth that can be reinvested, spurring innovation and more expansion—a self-reinforcing cycle of prosperity.

Yet, growth is becoming more elusive, inequitable and environmentally destructive, and the reassuring narrative of perpetual progress driven by growth is beginning to unravel. What if growth, the bedrock of our economic identity, is no longer guaranteed—or no longer desirable? It may be time to rethink our formula for prosperity. What if the focus shifted from the means of prosperity—growth—to its ends—wellbeing? Could we decouple prosperity from the relentless push for growth?

It’s a provocative thought, but one worth exploring if we are serious about prosperity and resilience. Let’s take a look at New Zealand’s, and the world’s, relationship with growth.

New Zealand is rich

New Zealand’s economy is growing (see figure 1). With a GDP of $252 billion in 2023, it’s the 68th largest economy in the world. But with a population of just 5.2 million, New Zealanders are among the world’s 50 wealthiest nationalities, ranked 44th, based on GDP per capita of $48,800. The United Nations classifies New Zealand as a developed, high income nation.

Figure 1: NZ GDP (current US$), 1960 to 2023 (World Bank)

Growth is a political pursuit

In New Zealand, the political strategy of promoting growth stretches back sixty years. In the 1950s, the country boasted a ‘rockstar’ economy, driven by ‘processed grass’ exports of meat, dairy and wool. During this period, New Zealand’s real GDP grew at an average annual rate of 4.4%, powered by ambitious public works, high export prices, agricultural innovation and a secure market in the UK. Unemployment was virtually zero, and the welfare system provided things like universal family benefits and subsidised mortgages for low income families.

Then came two huge shocks: in 1961, the UK applied to join the European Economic Community, and in 1966, wool prices collapsed due to a global shift towards synthetic fibres. New Zealand faced ruin. In response, Prime Minister Keith Holyoake set the country’s first-ever growth target in 1968, aiming for 4.5% annual growth over the next five years.

Since then, successive prime ministers have adapted the growth agenda to the times. In the 1970s, National’s Robert Muldoon introduced the ‘Think Big’ strategy focusing on national infrastructure projects. In the 1980s, Labour’s David Lange pushed through hard neoliberal reforms, which were further advanced by National’s Jim Bolger in the 1990s. In the 2000s, Labour’s Helen Clark pivoted to innovation, positioning New Zealand to ‘catch the knowledge wave’. As the 2010s unfolded, National’s John Key navigated the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis, championing foreign investment and tourism as ways to ‘lift our economic game’. Through the end of the decade, Labour’s Jacinda Ardern framed a ‘Wellbeing Budget’ as a sustainable and inclusive path forward. Now, National’s Christopher Luxon is intensifying the embrace of growth, with a focus on tourism, foreign investment, mining projects and appointing a Minister for Economic Growth.

A lifetime of evidence shows that both of New Zealand’s major political parties uphold the economic orthodoxy that long-term GDP growth is the ultimate measure of a healthy economy.

Pro-growth policies aren’t reversing growth’s slowdown

Despite long-term deployment of a wide variety of pro-growth policies, New Zealand’s GDP growth rate has steadily declined (see figure 2). Once the envy of the OECD, the country’s average annual growth rate since 2000 has been a modest 2.7%, but now sits at a mere 0.6%, trailing the OECD average of 1.7% and the world average of 3.2%.

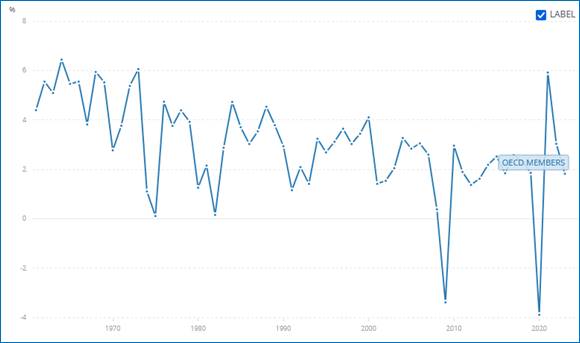

While New Zealand has slipped in the OECD ranks, its declining growth mirrors a trend across rich nations. In the 1960s, the average annual growth rate across the OECD was above 4%. During the 1980s and 1990s, it oscillated around 3%, but gradually drifted towards 2% in the 2010s and 2020s, with larger fluctuations due to the GFC and the COVID-19 pandemic (see figure 3).

Figure 2: GDP growth (annual %) New Zealand, 1960 to 2023 (World Bank)

Figure 3: GDP growth (annual %) OECD members, 1960 to 2023 (World Bank)

The field of economics struggles to explain the dynamics underpinning growth, with econometric models failing to account for different policy mixes working successfully in different countries at different times. There is no universal formula, no definitive playbook for growth. Free markets have long been hailed as the key to growth, but in New Zealand—one of the most open and deregulated economies in the world—they have not worked well.

There is no universal formula, no definitive playbook for growth.

Christopher Luxon’s approach to boosting GDP growth channels that of his political predecessor John Key, but overlooks the steps taken by Jacinda Ardern to build a more holistic sense of national prosperity beyond GDP, rooted in the Living Standards Framework, which was developed under Key. Luxon’s narrower focus may prove short-sighted. With New Zealand’s average annual rate of growth expected to stagnate below 2% this decade, the need for a broader definition of prosperity will only increase.

The longer term outlook for growth is highly uncertain. But one thing is clear: climate damages lag emissions by years, which means that past emissions will stifle future GDP growth. Meanwhile, modelling suggests that reaching global warming of 3oC would reduce global GDP by 10% on average and as much as 17% in some nations, compared to a world with no further climate change after today. It may soon become politically imperative to deprioritise growth metrics, focusing instead on wider prosperity metrics around wellbeing, equity and sustainability, to provide crucial assurances to both the public and the international community about the country’s economic resilience.

Yet, for now, the political emphasis remains firmly on finding GDP growth.

Productivity—the magic bullet New Zealand can’t find

Solow’s model, a keystone theory in mainstream economics, claims that economic growth can come not only from increased labour and capital inputs but also from improved efficiencies in their use (productivity)—more output from the same input. While labour and capital inputs tend to hit limits, productivity improvements, in theory, have no bounds. Hence, productivity improvement is seen as the key to sustained growth.

In New Zealand, low productivity growth has been a major contributor to the country’s declining rate of economic growth. This longstanding problem means New Zealanders work 20% more hours but produce 25% less GDP per hour than the OECD average—a situation that’s not expected to change in the next 3 to 5 years.

The Treasury Te Tai Ōhanga forecasts weak productivity growth. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand Te Pūtea Matua, too, projects limited annual output growth, between 1.5% and 2% through to 2028. The Growth Lab at Harvard University echoes this, predicting a 1.9% annual growth rate for New Zealand’s GDP through to 2031.

The Reserve Bank points to structural issues holding back productivity growth, including a small domestic market, foreign ownership in core sectors leaking profits overseas, weak investment into knowledge, and low foreign direct investment hindering adoption of new technologies and infrastructure improvements. Meanwhile, the Growth Lab’s outlook highlights the concentration of exports—and skills and knowhow—in low complexity sectors like tourism, dairy, meats, produce and forestry, offering limited opportunities for diversification into higher productivity industries like textiles, electronics and machinery manufacture. Moreover, when commodity prices rise, the value of the NZ dollar rises, pricing out more complex, higher value export goods.

The Productivity Commission, established in 2011 to examine New Zealand’s so-called productivity paradox—neoliberal policies co-existing with stagnant productivity—found that while past productivity gains had led to higher real wages, the labour income share of the gains had dropped between 1978 and 2010, while capital owners saw their share increase. Much of that wealth gain has flowed into the housing market, where tax-free capital gains accumulate, contributing to extreme housing unaffordability and chronic underinvestment in more productive sectors. As a result, New Zealand’s political economy has earned the moniker of “housing with bits tacked on”.

Short-term growth versus long-term prosperity

In 2024, New Zealand disbanded its Productivity Commission, replacing it with a new Ministry for Regulation tasked with boosting business growth and efficiency through refining the regulatory environment. However, if the Ministry neglects to examine the critical relationship between productivity and its broader societal outcomes—a central focus of the Productivity Commission—there’s a real risk that growth could be treated as an end in itself. This is already evident in the government’s encouragement of sectors like tourism and mining, which contribute to business wealth but offer little to society.

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, New Zealand tourism’s rebound was remarkable—contributing to 3.7% of GDP in 2023 (up 31%), 11.4% of exports (up 9%) and 6.7% of employment (up 48%). A less rosy reality lies beneath these buoyant figures. While tourism fuels GDP growth, the jobs it creates are low wage. It is resource intensive, straining infrastructure, creating traffic congestion, damaging the environment and exacerbating housing deprivation. It changes the very nature of places. Ramping up tourism, as the government is campaigning to achieve, is neither a solution to the productivity paradox, nor a means to social progress.

The government aims to double mining exports within a decade, positioning critical minerals, including coal extraction, as a high-growth opportunity generating regional jobs. The reality is more complex. Mining may have New Zealand’s highest rate of labour productivity—measured as GDP per full-time job—but it is not a significant employer, providing only 2,000 full-time jobs in 2023. Moreover, future productivity gains in mining are uncertain, and the industry’s particularly low complexity means that its expansion does not contribute to the high complexity diversification that could spur New Zealand’s economic growth. Mining’s capital intensive nature makes it vulnerable to economic slowdowns, reducing economic resilience, and forces the sector to rely on overseas investment, which comes with inherent risks. Foreign investors naturally siphon profits offshore, but they also exploit New Zealand, exaggerating contributions to the economy, receiving considerable tax breaks and paying little in royalties, while leaving legacy environmental risks. Meanwhile, granting private rights to mine stewardship land and commons seabed, while rolling back environmental protections, echoes the painful experiences of Māori with unfettered capitalism, and shows no sign of lessons learned. Expanding mining would generate GDP growth, profits and a small number of well-paid jobs in regional areas, but comes at a steep price to society.

New Zealand’s current story of prosperity is told through the Living Standards Framework dashboard—a broad set of indicators beyond GDP to inform government policy and investment decisions. There are upward trends in financial and physical capital, international investment, consumption, average household net worth, disposable income, employment rate and hourly earnings. This makes sense because New Zealand’s GDP is generally rising.

But the majority of indicators of human, social and environmental wellbeing are trending in the wrong direction, including cultural belonging, voter turnout, loneliness, mental health, healthcare affordability, rent affordability, food insecurity, financial insecurity, child poverty, youth skills, work-life balance satisfaction, family violence, subjective wellbeing, fish stocks, annual average national temperature and sea level rise.

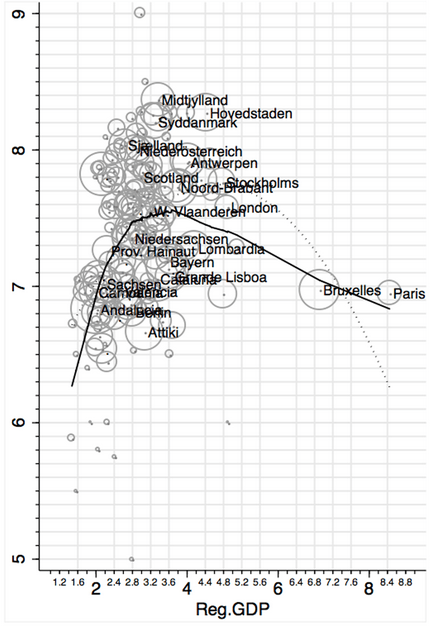

New Zealand’s high GDP and reducing life satisfaction contradicts the common sense that wealthier societies have greater wellbeing. But the fact is that life satisfaction increases with wealth in poor societies, levels off in rich societies and declines once societies become very rich (see figure 4). The bliss point for life satisfaction is around US$30,000 GDP per capita. New Zealand is well above this mark, with a GDP per capita in the region of US$47,000-$49,000.

Figure 4: Average life satisfaction and aggregate incomes in EU regions, using data from 1994 to 2008 (Proto and Rustichini, 2013)

New Zealand’s prosperity downturn—or social recession—won’t reverse if the costs and risks of business growth are shifted onto New Zealand society in the shape of low wages, declining living standards and environmental damage.

Unfortunately, this goes largely unchallenged, as there’s a prevailing belief that business growth comes first, creating individual wealth, and national wellbeing will follow. The boost in New Zealand’s GDP growth and national wellbeing after WW2 really cemented this idea, although it has never been repeated. The narrative is now so entrenched that hard times are rarely seen to be a result of poor quality growth; but rather, of not enough growth, giving licence to an unbridled pursuit of growth.

Hard times are rarely seen to be a result of poor quality growth; but rather, of not enough growth.

With New Zealand’s cost of living soaring, home ownership slipping out of reach, living standards in decline and emigration at record highs, the government is enthusiastically driving plans for growth offering immediate relief—like jobs in tourism—even when those plans are arguably hollow, failing to offer lasting benefits to households and communities and deepening economic fragility.

Empirical evidence tells us that GDP growth contributes very little to changes in household income. For it to have a lasting positive impact on national wellbeing, it must translate into greater financial security, improved living standards and widespread optimism. In short, growth is not inherently good, and there’s more to economic management than “going for growth”.

Ignoring the longer term, wider impacts of growth plans is reckless, and dismissive of expert warnings about the risks posed by social, technological, geopolitical and environmental forces unleashed by growth, as well as the scientific knowledge available to anticipate and manage these threats.

Good quality growth—various pathways to an ideal

It’s always been the case that certain economic activities, unchecked, will lead to poor outcomes for people and their surrounds. In 19th century Britain, for instance, the rise of trade unions and smoke abatement societies was a direct response to the rapid expansion of exploitative, dirty industries. But it wasn’t until 1987 that the notion of sustainable development—balancing growth, society and the environment—was articulated by the United Nations in the Brundtland Report. In 2015, the sustainable development and human rights agendas converged in global Sustainable Development Goals, setting 2030 targets for increasing economic growth and decreasing social and environmental ills.

The 2030 Agenda has drastically faltered. Only 17% of the 169 SDG targets are on track, with some even regressing. The pandemic slowed down efforts, but underlying inadequacy reflects the challenge of chasing single issue targets in a world of complex, interwoven issues and entrenched inequality. Modelling suggests only half of SDG targets are achievable by 2030, and vulnerable nations will achieve none, facing a $4 trillion investment gap, on top of mounting debt.

The 2030 Agenda is resetting, focusing on leverage, gaps in the framework and systemic opportunities. This involves shifting focus from end goals like eradicating poverty and providing equal opportunities to structural reforms around human rights, such as inclusive governance and equity of outcomes. Efforts to monetise ecosystem services and conserve vast areas of nature are being succeeded by discussions about the rights of nature and those inhabiting it. In 2024, the United Nations adopted the Pact for the Future, reaffirming the 2030 Agenda and multilateralism, calling for sustainable, inclusive, resilient economic growth with an emphasis on developing countries, and making new commitments, including a Global Digital Compact and a Declaration on Future Generations.

Meanwhile, the World Economic Forum is worried about the pace of growth, suggesting that alignment with these other global priorities would “complete” the growth agenda—in other words, de-risk growth. WEF’s Future of Growth framework calls for evaluating the quality of growth with measures of innovativeness, inclusiveness, sustainability and resilience. Assessing the global economy as halfway towards this growth ideal, WEF highlights the different growth pathways forward. Richer nations must grow sustainably, while middle income nations, already showing economic resilience, and low income nations, demonstrating sustainability, need their growth to reflect other pillars.

No nation meets basic needs while using resources sustainably.

Ecological economists show that no nation meets basic needs while using resources sustainably (see figure 5). To achieve a socio-ecological ideal (green ‘doughnut’, top left), this research, too, suggests different pathways are needed, largely distinguishing high, medium and low income nations. Rich nations are clustered to the top right, operating grossly unsustainable economies, yet failing to meet some basic needs.

Figure 5: Number of social thresholds achieved versus number of biophysical boundaries transgressed for different countries, scaled by population (O’Neill et al, 2018)

WEF admits that growth and sustainability are “highly divergent”. Despite its mission to develop collaboration on global progress, hosting a gathering for thousands of experts and leaders annually at Davos, WEF offers no direction—a worrying failure of leadership. Instead, WEF makes reference to decoupling, the theory behind green growth, but notes that scepticism that surrounds it.

Green growth—is it even possible?

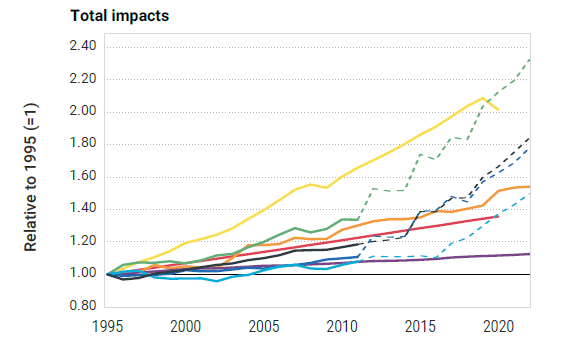

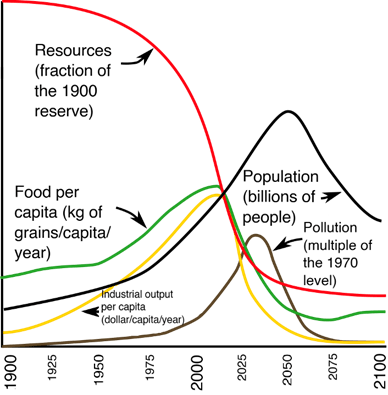

Throughout the industrial era, economic growth has driven rising resource use and environmental pollution—known as the ‘Great Acceleration’—changing Earth systems and escalating risks to humanity. Even so many decades after the landmark 1962 book Silent Spring raised alarms about the environmental harms of industrial chemicals, impacts continue to accelerate (see figure 6).

Figure 6: Population, GDP and environmental indicators, 1995 to 2022 (UNEP International Resource Panel)

Decoupling theory proposes that global GDP can grow while reducing these risks by slowing down resource use (relative decoupling) and decreasing environmental pollution (absolute decoupling).

This theory was preceded by the Environmental Kuznets Curve, since discredited, which suggested that pollution increases with national income to a point, then decreases as income grows further.

Decoupling theory first emerged in 2011 via UNEP reports, quickly shaping climate policy. However, the scientific community argues that decoupling lacks sufficient evidence to underpin policy. To meet this burden of proof, decoupling must be absolute, permanent and just, and align with global goals.

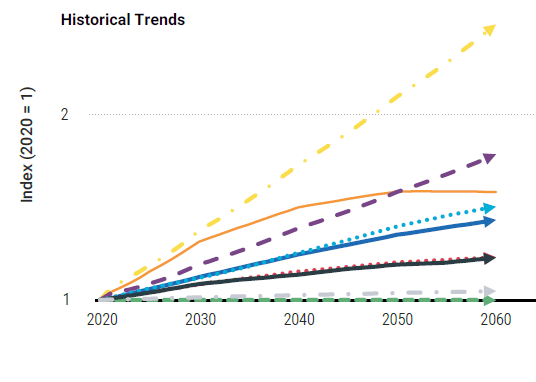

UNEP’s latest scenarios for 2060 show that under a historical trends pathway (see figure 7), GDP would grow 150%, increasing human development by 44%, but environmental impacts would also surge—with extraction 59% higher, biomass extraction 79% higher, primary energy use 51% higher and GHG emissions 23% higher.

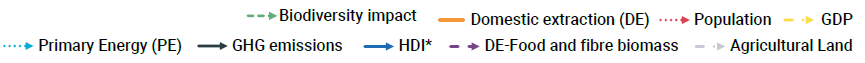

In contrast, a sustainability transition pathway (see figure 8) would increase GDP by 158% and human development by 53% and lower emissions by 83%—with extraction just 17% higher, biomass extraction 31% higher and primary energy use 27% lower.

Figure 7: UNEP Historical Trends scenario, 2020 to 2060 (UNEP International Resource Panel)

Figure 8: Projected UNEP Sustainability Transition scenario, 2020 to 2060 (UNEP International Resource Panel)

Various demand-side shifts avoid additional resource use. Resource shifts include material efficiencies, sustainable housing, urban design, mobility and responsible production. Climate shifts include energy efficiency, electrification, renewable energy and carbon removal. Food shifts involve healthy diets, zero hunger, reduced food waste and ecological protections.

Without a doubt, these shifts are necessary to any sustainability approach, but do the decoupling claims of the scenario meet the burden of proof for policymaking?

Figure 9: Sustainability transition scenario, resource use, 2020 to 2060 (UNEP International Resource Panel)

UNEP’s sustainability transition scenario does not demonstrate absolute, permanent decoupling. Resource use rises from 102 billion tonnes in 2020 to 120 billion tonnes in 2045, then declines to 115 billion tonnes by 2060 (see figure 9). With GDP growing faster, this reflects relative decoupling until 2045, followed by absolute decoupling from 2045 to 2060. Helpfully, this scenario accounts for the rebound effect, where savings from efficiencies lead to higher consumption, addressing a common criticism of decoupling scenarios. However, scientists warn that once resource efficiencies hit physical limits, GDP growth will drive up resource use again. UNEP does not reveal post-2060 projections or make any suggestion that absolute resource decoupling can be sustained as GDP continues to rise.

The sustainability transition scenario addresses climate goals well, but not nature goals. The Paris Agreement aims to limit global warming to well below 2°C, ideally 1.5°C, and requires reaching net zero emissions by 2050. The sustainability transition scenario aligns with the IEA Net Zero Emissions by 2050 scenario, with fossil fuel use dropping nearly 60% and GHG emissions by over 80% by 2060. However, it falls far short of meeting the goals of the Global Biodiversity Framework (2022) and the UN Convention to Combat Desertification. UNEP itself suggested in 2014 that sustainable material use is 6-8 tonnes per capita per year—70 billion tonnes for 10 billion people in 2060. At 115 billion tonnes, the sustainability transition scenario far surpasses the sustainability threshold, and drives two thirds of the biodiversity loss expected if BAU were to continue.

The scenario has marginal justice outcomes. While it leads to greater wellbeing gains for lower income nations and greater reductions in resource use from wealthier ones, global sufficiency (a form of distributive justice) remains only marginally served. Material footprints per capita rise in lower income nations from 5-6 tonnes to 7-8 tonnes (which could support a decent living standard), while falling in higher income nations from 20-22 tonnes to 17 tonnes—still a vast gap. Additionally, demand for minerals critical to the clean energy transition will surge, creating new sites of extraction and processing and raising new risks of environmental injustice.

The sustainability transition scenario fails to prove that decoupling effects would be absolute and permanent. While it aligns with the Paris Agreement, it leaves humanity vulnerable to biodiversity loss, and though it slightly improves distributive justice, it opens new avenues for environmental injustice. This scenario fails to meet the burden of proof required to underpin policy for a safe and just global economy.

GDP-GHG decoupling does occur in some wealthy nations. It’s a positive step, demonstrating that some national scale green growth is possible. The UK, for instance, has made notable progress. However, we must cut through the hype to gain a clear perspective. Rich nations’ decarbonisation is slower than required to meet their fair share of global carbon budgets for 1.5°C and 2°C (see figure 10). With the net zero deadline just 25 years away, at current decarbonisation rates, rich nations would take an average of 220 years to reduce their 2022 emissions by 95%, a level at which negative emissions technologies could feasibly operate. Decoupling is locally and temporarily possible, but that doesn’t prove the path is feasible for all countries, which face numerous barriers.

Some national scale green growth is possible…but that doesn’t prove it’s sufficient, permanent or feasible for all countries.

Figure 10: Rich nation rates of GDP-CO2 decoupling, comparing BAU and 1.5°C fair share projections (Vogel & Hickel, 2023)

It’s becoming clear that aggregate GDP growth hinders climate and nature goals. The window for wealth building through metabolic growth has closed, and continuing with green growth policies is a risky social gamble.

The window for wealth building through metabolic growth has closed.

Without falling prey to doomism, we must still confront the worst scenario consequences of failing to meet global sustainability deadlines, and prepare more than one pathway to a sustainable economy.

Global growth—what could go wrong?

Earth scientists view our planet and its atmosphere as a thermodynamic system with finite materials, exchanging energy with space. The Earth system is in constant renewal, powered by the sun’s infinite energy, fuelling cycles of replenishment across timeframes—from days for plant growth to eons for fossil fuel formation.

Mainstream economics neglects the laws of thermodynamics, which is ironic given that Nobel prize-winning economist Paul Samuelson developed economic analysis in the mid-20th century based on thermodynamic principles, leading economics to insist upon mathematical models and to treat its theories as natural laws, despite failing to meet the rigorous standards of science.

Societies interact with the Earth system, using materials and energy while generating pollution, a socio-environmental relationship known as the social metabolism. Sustainable economic activity aligns with natural cycles, unsustainable activity pressures them. For instance, species depletion can lead to long recovery periods, or even extinction.

Some materials are effectively finite—non-renewable within human timeframes—such as metal ores, non-metallic minerals and fossil fuels. The global economy increasingly depends on non-metallic minerals like sand and gravel for infrastructure, with their share of global extraction rising from one-third to one-half between 1970 and 2020. This will grow further, from 50 billion tonnes in 2020 to at least 70 billion tonnes by 2060 (see figure 9).

Economies reliant on finite materials cannot follow a linear path indefinitely. As resources become harder to access, growth slows, plateaus and eventually reverses. This applies to both fossil fuel and renewable energy-based economies, as finite materials are required to convert renewable energies into usable electricity.

Circular economy is a vital cog in sustainability. Currently, only 9% of the economy is circular, but could surpass 30%. An economy that builds less and uses less fossil fuel energy could achieve even higher circularity. However, social metabolism is subject to the laws of thermodynamics, including entropy, which dictates that as materials are transformed, their quality declines. Thus, no economy can be fully circular—some extraction will always be necessary to replace degraded materials needed for essential goods.

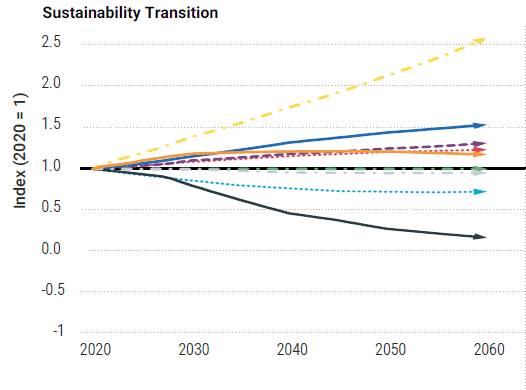

The 1972 Limits to Growth (LtG) report was groundbreaking in using world systems modelling to illustrate the dynamic relationships between economics, materials and ecosystems. LtG outlined a number of future pathways. While simplistic, these pathways, like the UNEP scenarios above, offer insights into the outcomes of different economic strategies.

Controversially, the business-as-usual (BAU) pathway led to depletion of finite resources (see figure 11, red line). Another scenario based on technological advancement (BAU2), which doubled resources through circularity, led to unmanageable pollution some decades later. Hitting resource and pollution limits respectively, both BAU and BAU2 projections then showed sharp declines in food production, population and industrial output (see figure 11, black, green and yellow lines). LtG’s sustainability scenario, however, proposed stabilising global population, limiting industrial output, increasing recycling and curbing pollution to avert these declines.

Figure 11: Limits to Growth standard run (business-as-usual) projection, 1972 (Meadows et al , 1972)

LtG divided expert opinion, sparking the modern sustainability movement while entrenching mainstream economics theories that material scarcities can always be overcome by human ingenuity. Neoclassical growth theory, based on Solow’s model, argues that long run economic growth comes from labour and capital inputs and efficiencies, with limitless potential for the latter. Endogenous growth theory contends that innovation and investment in human capital drive growth. In both cases, human ingenuity is seen as the ultimate enabler of growth, finding ways to expand into new frontiers and endlessly extract, refine and substitute materials.

Since LtG was published, global economic growth has continued to climb exponentially (see figure 12), and the notion of finite resource constraints has failed to convince as a serious economic threat. For instance, while studies show that depletion of oil and gas reserves is only decades away, the International Energy Agency assumes that fossil fuel depletion will be delayed by developing more complex reservoirs and adopting new, more efficient technologies.

Figure 12: World GDP per capita (current US$), 1970 to 2023 (World Bank)

Yet, data from the past 50 years shows that the LtG scenarios are still unfolding. Recent updates to LtG models suggest the global economy is stuck between the BAU and BAU2 tracks, and is rapidly losing the chance to transition to a sustainability pathway. Population is now projected to peak later and at a higher number than originally forecast. On the BAU track, resource depletion remains the key trigger for the collapse of food, population and industrial output. On the BAU2 path, pollution is expected to drive the collapse of industrial output and food production later this century.

Resource and pollution limits are followed by sharp economic declines.

Regarding the effects of pollution, the planetary boundaries framework offers clarity, identifying thresholds for Earth system indicators linked to the ‘safe’ Holocene epoch. Breaching these thresholds signals systemic risks to Earth’s stability, with six of nine already surpassed—biodiversity loss posing the greatest risk to human systems (see figure 13). Recall that biodiversity loss is an area that UNEP’s sustainability transition scenario made worse.

Figure 13: Status of nine planetary boundaries, 2023 (Richardson et al, 2023)

New Zealand’s economy far exceeds its fair share of planetary boundaries. It operates at 5 to 6.5 times its fair share of the safe threshold for tCO2 per capita per year. It takes up 1.25 times its fair share of the safe threshold for land use change, due to the loss of more than half of the country’s original forest cover, now mostly replaced with pastureland. It runs at 1.9 to 2.1 times its fair share of the safe threshold for freshwater use. Its production-based levels of nitrogen and phosphorous use are far higher than the OECD average, making New Zealand the world’s 6th largest exporter of nitrogen. It has outrun its fair share of the safe threshold for biosphere integrity by a factor of 3.4.

Change is happening fast. Early warnings must not be ignored.

The crucial message from LtG scenarios, planetary boundaries and ‘great acceleration’ data is clear: change is happening fast, and early warnings must not be ignored. These frameworks highlight that failing to substitute depleted or highly polluting materials critical to essential economic activities could trigger rapid industrial decline.

Growth-dependent wellbeing undermines resilience

There’s a significant divide in attitudes between disciplines. For environmentalists, the need to abandon fossil fuels is crystal clear. Climate goals demand that 60% of oil and gas and 90% of coal remains in the ground. So, they ask: why the delay?

Mainstream economists, however, are fixated on preserving economic growth during the clean energy transition. Growth stabilises the global economy, while its absence—recession or depression—creates instability. While environmentalists’ warnings are not ignored, economic stability is the more immediate priority. Wellbeing systems, such as employment, pensions and public financing of infrastructure, are intrinsically growth-dependent. They require a positive growth rate in order to function.

To build economic resilience, these systems must be decoupled from growth. Take employment, for example. As GDP rises, unemployment falls—but recession leads to rising unemployment. Thus, employment rates are growth dependent. But the functions of employment are livelihoods, social security and social inclusion. The objective is to provide these functions of employment outside the growth-based system—stabilising employment in the event of a low, zero or negative growth economy. Policy suggestions include fairly distributing access to work through work time reduction and job guarantee schemes, providing social security through universal basic income and services, and building social inclusion through prioritising the care economy.

If wellbeing systems were independent of growth, a period of negative growth would be a technical recession, not one felt by society. This could unlock resilience, enabling us to prioritise good growth over bad—even if that means a net contraction in GDP.

However, the government is pushing to increase the amount of wellbeing services supplied by the private sector. Since the private sector drives growth, this further deepens the growth dependence of wellbeing.

Cultivating a new option for prosperity—without growth

New Zealand’s economy, among the richest per capita globally, has long been ‘anti-prosperous.’ Prosperity isn’t just capital growth, but also human, social and environmental wellbeing. The nation’s wellbeing systems lack resilience in the face of inevitable periods of low or negative GDP growth; a vulnerability deepened by privatisation. Furthermore, New Zealand’s consumption of planetary resources is at odds with global sustainability. Accelerating nature loss is an early warning, so far unheeded in policy and business, of the potential for a sharp economic decline in our foreseeable future. It’s a tale of two economies: one for capital—enjoying freedom to grow, albeit struggling to achieve it—and another for society—steadily losing ground.

To chart a resilient, prosperous new path, New Zealand must move beyond the narrow confines of growth for growth’s sake—and the lack of imagination that comes with it.

The current government’s focus on growth is hardly innovative or courageous. Its hardline neoliberal approach, heavily influenced by Project 2025, the policy playbook guiding Donald Trump’s administration, is an intensification of ideas that are 90-years old. There’s little to admire in the fast pace of change, eschewing democratic oversight, with the confidence of 40 years of neoliberal consensus behind them, and lessons learned from the 1980s on how to force these ideas onto society. Wrapped in chaos, what seems revolutionary is in fact more of the same.

Our political economy is overdue a radical rethink. Climate goals, nature goals, inequality, social division—all call for it. The outdated notion that growth is inevitable—or that simply distinguishing between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ growth will still lead to net growth—needs to be filed under ‘things we once believed to be true’. Human ingenuity, the ultimate enabler of growth, can alternatively enable a post-growth economy. It’s time for New Zealanders, experts across many sectors—all long accustomed to going with growth assumptions—to let go just a bit and start to explore the opportunities for prosperity without growth.

The conversation has already begun. Check out the links below for more insights—and explore the pages of Heliocene, too.

WEALL Aotearoa Wellbeing Economy Alliance

Māori economies and wellbeing economy strategies: A cognitive convergence?

Post-growth: the science of wellbeing within planetary boundaries

Featured image by NASA.